Check out a series of video reporting from Greece by the Reelnews network, “an activist video collective, set up to publicise and share information on inspirational campaigns and struggles.”

Look at their playlist for the following short videos:

1) Our Present is Your Future: How to destroy public health services (Reel News) Over a third of hospitals to close. Exhorbitant charges. Healthworkers not being paid. But doctors are leading an astonishing fightback.

2) It’s still like being in a war zone — Immigrants in Greece (Reel News)

3) Crisis (Reel News) Don’t believe the lies — the Greek public debt is down to the banks and the rich. With extracts from the film “Debtocracy”.

4) That’s Our Power — Rank and File Organising (Reel News) The growth of rank and file committees, featuring the three longest all out strikes ever in Greece (steel factory, national newspaper & TV station), plus hospital occupations.

5) Solidarity — Not Charity: Community Organising (Reel News) Local assemblies are springing up all over Greece, organising community kitchens, clothing exchanges and other acts of practical solidarity.

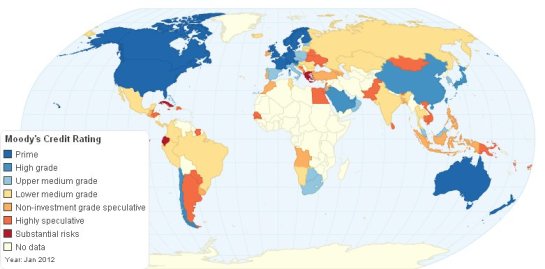

Problem? What Problem?

Problem? What Problem?